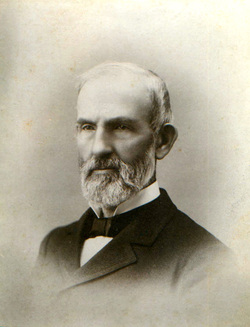

James Clark McGrew (1813-1910)

James C. McGrew 1813 - 1910

One of West Virginia's forefathers, the Honorable James C. McGrew was a humble man who was thrust into greatness by the circumstances of his day. Born September 14, 1813, he began life simply enough as the son of Col. James C. and Isabelle Clark McGrew. He worked on the family farm in Brandonville, Virginia, and attended the local one-room school through his adolescence, when, at age 19, he became a clerk for brothers Harrison and Elisha Hagans. Assigned to the Kingwood store, he learned the mercantile trade so well that he eventually established his own store. He also married Harrison's daughter Persis, and the new couple made their home in Kingwood.

Though McGrew never sought public acclaim during his lifetime, he was often enlisted into public service by local govening bodies. He had a "knack" for building things. Not only had he designed and built a home for his bride in 1841, but he also constructed the Preston Academy shortly after that. Later, in 1856, he was asked by the County Court to construct a bridge across the Cheat River and the new court house when other contractors' bids were beyond their budget.

He was also an entrepreneur who expanded his family's business by building the first general stores in Reedsville and in Tunnelton. He also ventured into coal mining, operated a tannery, became an agent for two different local train companies, and as his crowning achievement, co-founded the National Bank of Kingwood.

By 1861, McGrew had earned a sound reputation that led to his nomination and election as one of Preston County's two representatives to the Virginia Convention, where secession from the Union was to be debated and decided. McGrew was the leading Republican; William G. Brown, Sr., was the leading Democrat, who was already a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia. The two traveled to Richmond with other western county representatives and, from February through April 1861, joined in the argument to reject secession and stay within the Union. They faced great peril in taking such a stance. As tensions built following the assault on Fort Sumter, loyal Unionists were harassed, threatened, taunted, and, as happened one night to McGrew and his immediate colleagues, visited at night by a mob that hoisted a hangman's noose in a nearby tree.

Not to be deterred, though, McGrew and 54 others consistently voted against secession.

However, on April 17, Secessionists took the day with 88 who favored seceding from the Union. A state-wide election was scheduled for the following May. Not yet willing to conceed, McGrew and others quietly organized a movement that became the Reorganized (later Restored) Government of Virginia, which met in Wheeling in June 1861. That body initiated the Statehood Movement which resulted in the admission of West Virginia as the 35th State of the Union on June 20, 1863. McGrew served in both the First and Second Legislatures and went on to become a member of the House of Representatives in the 41st and 42nd Sessions of Congress. Though he retired from national politics in 1873, he continued to receive requests for endorsements from other candidates of the day, but he consistently declined invitations to appear on party platforms.

Instead, he gave his time and energies to local civic service. He had already served as Kingwood's Mayor prior to the War; after returning from Washington, he was re-elected four more times. As the Council's executive officer, he drafted the first City Ordinances which were later adopted and enforced. He also returned to his familiar role as leader within the Kingwood Methodist-Episcopal Church and not only oversaw the construction of the church's 1879 structure, but traveled to Baltimore to purchase the 800 lb. bell that still hangs in the church's tower.

His energy, drive, and commitment were unfailing and are evident in his devotion to his bank, which survived well into the next century and closed as a result of the Great Depression. But under McGrew's leadership as Head Cashier and later President, it was a sound and trusted institution. McGrew personally oversaw the operations from 1865 forward and was once again at the forefront of his day by consistently adopting the newest technology for calculating and protecting the Bank's assets. Even into his 96th year of life, McGrew was engaged in plans for expansion and approved the blueprint for a new more modern bank building. Though he never lived to see the completed structure, it still stands today and, along with his home "The Pines," serves as a lasting reminder of McGrew's courage, foresight, and influence.

Though McGrew never sought public acclaim during his lifetime, he was often enlisted into public service by local govening bodies. He had a "knack" for building things. Not only had he designed and built a home for his bride in 1841, but he also constructed the Preston Academy shortly after that. Later, in 1856, he was asked by the County Court to construct a bridge across the Cheat River and the new court house when other contractors' bids were beyond their budget.

He was also an entrepreneur who expanded his family's business by building the first general stores in Reedsville and in Tunnelton. He also ventured into coal mining, operated a tannery, became an agent for two different local train companies, and as his crowning achievement, co-founded the National Bank of Kingwood.

By 1861, McGrew had earned a sound reputation that led to his nomination and election as one of Preston County's two representatives to the Virginia Convention, where secession from the Union was to be debated and decided. McGrew was the leading Republican; William G. Brown, Sr., was the leading Democrat, who was already a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia. The two traveled to Richmond with other western county representatives and, from February through April 1861, joined in the argument to reject secession and stay within the Union. They faced great peril in taking such a stance. As tensions built following the assault on Fort Sumter, loyal Unionists were harassed, threatened, taunted, and, as happened one night to McGrew and his immediate colleagues, visited at night by a mob that hoisted a hangman's noose in a nearby tree.

Not to be deterred, though, McGrew and 54 others consistently voted against secession.

However, on April 17, Secessionists took the day with 88 who favored seceding from the Union. A state-wide election was scheduled for the following May. Not yet willing to conceed, McGrew and others quietly organized a movement that became the Reorganized (later Restored) Government of Virginia, which met in Wheeling in June 1861. That body initiated the Statehood Movement which resulted in the admission of West Virginia as the 35th State of the Union on June 20, 1863. McGrew served in both the First and Second Legislatures and went on to become a member of the House of Representatives in the 41st and 42nd Sessions of Congress. Though he retired from national politics in 1873, he continued to receive requests for endorsements from other candidates of the day, but he consistently declined invitations to appear on party platforms.

Instead, he gave his time and energies to local civic service. He had already served as Kingwood's Mayor prior to the War; after returning from Washington, he was re-elected four more times. As the Council's executive officer, he drafted the first City Ordinances which were later adopted and enforced. He also returned to his familiar role as leader within the Kingwood Methodist-Episcopal Church and not only oversaw the construction of the church's 1879 structure, but traveled to Baltimore to purchase the 800 lb. bell that still hangs in the church's tower.

His energy, drive, and commitment were unfailing and are evident in his devotion to his bank, which survived well into the next century and closed as a result of the Great Depression. But under McGrew's leadership as Head Cashier and later President, it was a sound and trusted institution. McGrew personally oversaw the operations from 1865 forward and was once again at the forefront of his day by consistently adopting the newest technology for calculating and protecting the Bank's assets. Even into his 96th year of life, McGrew was engaged in plans for expansion and approved the blueprint for a new more modern bank building. Though he never lived to see the completed structure, it still stands today and, along with his home "The Pines," serves as a lasting reminder of McGrew's courage, foresight, and influence.

McGrew died in his beloved home at 9:00 on a September Sunday morning, four days after his 97th birthday. His passing was noted in newspapers across the nation because he was, at that time, the oldest former-Congressman in the land. His role in West Virginia's statehood was recalled for another generation to appreciate. In his home community, tributes filled two pages and more in the local newspaper. He was remembered not only for his distinguished service to West Virginia, but also for his depth of thought, personal gentility, and noble character. On the day of his funeral, Mayor Elias Lantz ordered that businesses close for a two hour moratorium in McGrew's honor. He was laid to rest in the McGrew family plot, next to his beloved wife Persis, in Maplewood Cemetery in Kingwood.